It’s time for governments to reconsider the long-held premise that investing in events should be based on achieving pre-determined outputs like visitation, writes Stu Speirs.

Earlier in the year, I opined on the need to reprioritise how Governments invest in events. That thought bubble focused on arguing for a reprioritising of the benefits (or outputs) driven by events and a re-think of how success is defined more generally.

Following on from that, this piece questions how governments invest in events, specifically “place-based events” that are locally owned and grounded in local culture and community.

In short, I’m questioning the long-held premise of investing in events based on achieving pre-determined outputs (e.g. visitation) and arguing for government investment to be focused on strengthening an event’s key inputs.

Before I get to what I mean by inputs, let’s touch on what’s at the heart of an outputs-based approach and philosophy.

Outputs based-approach

When thinking in terms of event acquisition, investing based on driving certain outputs (e.g. visitation, civic pride, social equity) makes sense as the events being acquired will have a track record – existing awareness and brand equity.

Want to bring Manchester United to your city? You’ll need to pay for the enormous brand equity they bring to the table. Like the sound of having South by Southwest in your backyard? There’ll be a hefty price to pay for its unparalleled reputation built over more than thirty years. Fancy hosting the Australian Schools Volleyball Championships? You’ll need to pay for the 40 years of hard work that now sees it regularly attract over 5,000 participants and their entourage every year.

This acquisition approach is pretty simple. Pay something and get a relatively surefire set of outputs in return.

History says that if you want your place to have its very own Vivid Sydney, Melbourne Cup, Elvis Festival or Echuca Winter Blues, then you should invest for a minimum of five years and do so without expecting a significant return in visitation as an output.

The problem I see time and time again however, is governments of all levels using this same approach to invest in locally grown, place-based events when they are a completely different kettle of fish. Why our governments predicate their investment in locally owned and grown events in a comparable manner to acquired events is simplistic and fails to recognise history and how major events come to be in the first place.

This desire to see outputs – primarily economic impact via visitation – in exchange for investment in place-based events, particularly those in their nascent years, risks the chance of sustainable, long-term success. It diverts the focus from where it should be – the inputs at the heart of underlying operational and brand health.

History tells us that place-based events need a minimum of five years before leveraging them to deliver key outputs such as visitation can be considered. Here are some well-known examples:

Vivid Sydney

Having started in 2009, the third year of Vivid Sydney in 2011 drove relatively modest visitation and economic impact, particularly given the size and scale of investment from various levels of government.

As part of the team at Events NSW at the time, I recall that the argument to extend the event’s funding beyond the initial three-year term was an uphill one. When we were able to drive up to $20 in direct overnight visitor spend for every $1 dollar we were spending to acquire some other existing events, why would the government continue investing in Vivid Sydney, which was failing to yield anywhere near that sort of return in economic terms?

Thanks to the leadership at Events NSW at the time – and an argument based largely on the civic pride Vivid inspired amongst Sydneysiders who were aware of it – funding was secured for subsequent years.

By years four and five (2012 & 2013), the event’s awareness and brand equity had built to the point that visitation started to grow more rapidly. In turn, that growth ticked the much-vaunted economic impact box, and the event has gone on to become the nation’s largest, with the 2023 iteration attracting a cumulative attendance of almost 3.3 million people and a yet-to-be-confirmed but likely economic impact of up to $150m.

Echuca Winter Blues

The popular annual blues fest was started in 1999 by six local musos who got together for a Sunday afternoon jam. By 2008, after ten years it had grown organically and steadily to include 22 different artists across 18 local venues. From that point on, its growth has been more rapid, now attracting over 60 artists with an event footprint including 31 venues. Today, over 20,000 people attend across the four days of the event, doubling the population of Echuca Moama for that long weekend.

That slow, organic growth was fuelled by local drive and commitment to the event. It was only after the event was a proven success that Visit Victoria started to invest.

Parkes Elvis Festival

Dreamt up by a local couple and friend, the Parkes Elvis Festival celebrated its first iteration in 1993. The event attracted hundreds of people in the initial years, the vast majority of whom were locals. Far from an instant success at a local level, let alone amongst potential visitors, the event experienced anaemic growth in its initial years.

However, as its dedicated group of organisers persisted, it gradually started to win favour locally, and at about the ten-year mark, visitation started to rise. That ten-year mark also coincided with the first investment from Sydney-based Tourism NSW.

Today, it attracts over 20,000 people each and every year and is held up as a prime example of how an event can shift and build the social, economic and brand identity of a place.

Whilst there are always exceptions to the rule (the Deni Ute Muster drew significant visitation from very early on in its history), the list of major events that had comparable stories of gradual, slow growth in their early years is long.

The Australian Open of Tennis, The Australian Wooden Boat Festival, Cementa, The Unconformity, Grampians Grape Escape, the Stawell Gift, the Melbourne Cup Carnival, Mt Isa Rodeo, Gympie Muster, Floriade, Toowoomba Carnival of Flowers, Tamworth Country Music Festival are just a few that grew slowly or indeed struggled in their early years before going on to become what they are today.

Focus on inputs

So why is it that when the story of gradual, slow growth in the early years is almost ubiquitous across our nation’s most important events, that the nation’s primary investors in events, Tourism and Destination bodies not only predicate their investment on delivering visitation but do so with an absolute maximum of a three-year timeframe? History says that if you want your place to have its very own Vivid Sydney, Melbourne Cup, Elvis Festival or Echuca Winter Blues, then you should invest for a minimum of five years and do so without expecting a significant return in visitation as an output.

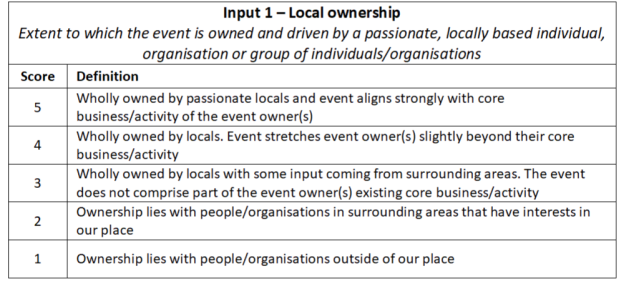

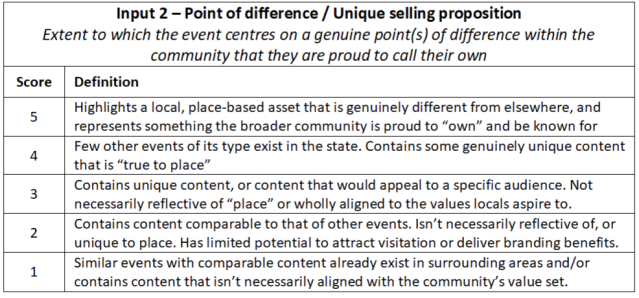

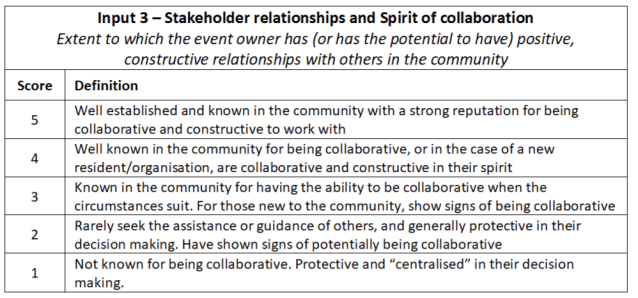

So, if we’re not going to predicate funding based on outputs such as visitation, then how do we make judgements on the events to fund? It’s at this point that I come back to the idea of investing in events that have certain “inputs” at their core, those inputs being threefold, namely;

1. the health of relationships they have within the community and a spirit of collaboration,

2. local ownership, and

3. content that puts a genuine point of difference at the heart of the event.

Taking those three fundamental inputs into what makes for a “healthy” event, I have written the 15-point assessment framework seen below. It is a genericised version of that which I now advise my clients to use when it comes to events grounded in local culture.

If we were to have scored each of the above-mentioned events in their early years using this framework, every single one would score somewhere between 13 and 15 out of 15. If we’d scored them based on visitation in those earlier years, few, if any would’ve stacked up. Note, too, that every single one of those events now delivers on the core metric of visitation and much, much more.

If your community wants events that are representative of what makes your place different then base your investment on strengthening the three inputs above and let the outputs, such as economic impact, look after themselves.

*Stu Speirs is director of SilverLining Strategy

Comment below to have your say on this story.

If you have a news story or tip-off, get in touch at editorial@governmentnews.com.au.

Sign up to the Government News newsletter