New research shows police and emergency services have disproportionately high rates of mental illness.

Two hours into his shift with NSW Ambulances in April 2018, paramedic Tony Jenkins took his own life, following a meeting with a senior ambulance officer about his alleged use of an opioid.

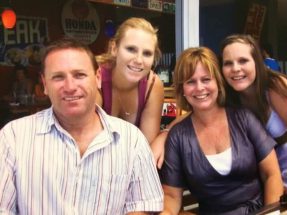

According to Mr Jenkins’ daughter, Cidney, although her father told staff in this meeting that he needed help, and hospitalisation was discussed, her father was dropped to his car alone at the conclusion of the meeting.

Ms Jenkins told Government News that her father’s death indicates “a series of complete failures” by NSW Ambulance for a death she says was preventable.

“I don’t believe my father had adequate mental health support during his 28 years as a paramedic, and what happened to him on 9 April couldn’t be a clearer example of the severity of the lack of duty of care towards him.”

A representative from NSW Ambulance extended their condolences to the Jenkins family, and said they can make no further comment on the circumstances of Mr Jenkins death, pending the outcome of ongoing investigations.

The representative told Government News that they take the mental health and wellbeing of staff “extremely seriously” and have a range of support services in place including peer support, chaplains and psychologists.

Ms Jenkins believes that emergency services need to train staff in suicide prevention and intervention, promote job rotations to manage excessive exposure to traumatic events and work to tackle the stigma around seeking help.

“The current culture of NSW Ambulance actively endorses motifs such as “sook leave” where paramedics are often scrutinised for asking for help or expressing mental health issues as a result of their work,” she says.

High rates found

Last month an Australian-first survey from beyondblue found that police and emergency workers have disproportionately high rates of mental illness and suicidal thinking compared to the rest of the population.

Of the 21,000 police and emergency services workers surveyed, one in three have high or very high psychological distress, and one in four ex-responders noted PTSD.

More than one in 2.5 employees and one in three volunteers also reported having been diagnosed with a mental health condition in their life compared to one in five Australian adults.

Most emergency services workers also reported more suicidal thinking and planning than the rest of the population, while 33 per cent reported shame about their mental health condition.

Holistic and targeted approach needed

On the back of these findings, a mental health expert has urged governments to respond to the harrowing data.

Nicole Sadler, director of military and high risk organisations at Phoenix Australia, Australia’s centre for posttraumatic mental health, says that agencies should be looking at developing holistic mental health strategies.

This means looking not only at addressing the specific trauma that police and emergency services often face, but also looking at addressing other workplace stressors, Ms Sadler tells Government News.

“First of all they need to be taking an organisational approach to what’s going on. What we’re seeing is over 50 per cent of people talking about exposure to traumatic events, which has deeply affected them,” she said.

While some organisations have “great systems” in place to improve the wellbeing of staff, others need targeted strategies as well as implementation plans, resources, policies and procedures, Ms Sadler said.

Organisations should be tracking the progress of strategies over time, making investments in “whole of career” programs and improving the mental health literacy of staff and family.

Whole of career programs and policies should cover the recruitment and induction process all the way to post-career support mechanisms, she said.

Share mental health resources

Engaging with organisations with existing skills or resources in mental health prevention and planning is critical for agencies to create effective strategies, Ms Sadler said.

Agencies should be reaching out to organisations with mental health expertise like beyondblue to inform their strategies.

The next phase of the study will see beyondblue working with participating agencies to help them apply specific learnings to their workplace mental health programs.

If this article has raised concerns for you contact Lifeline on 13 11 14.

Comment below to have your say on this story.

If you have a news story or tip-off, get in touch at editorial@governmentnews.com.au.

Sign up to the Government News newsletter.

Well done Cidney Jenkins. You speak with such dignity and clarity – it’s important that emergency services across Australia hear your message.

Useful research highlighting the high risk of experiencing psychological trauma in emergency service professions. Similar risks exist for military personnel.