There’s a lot of excitement around MaaS at the moment, but what is it and what’s in it for government? Government News investigates.

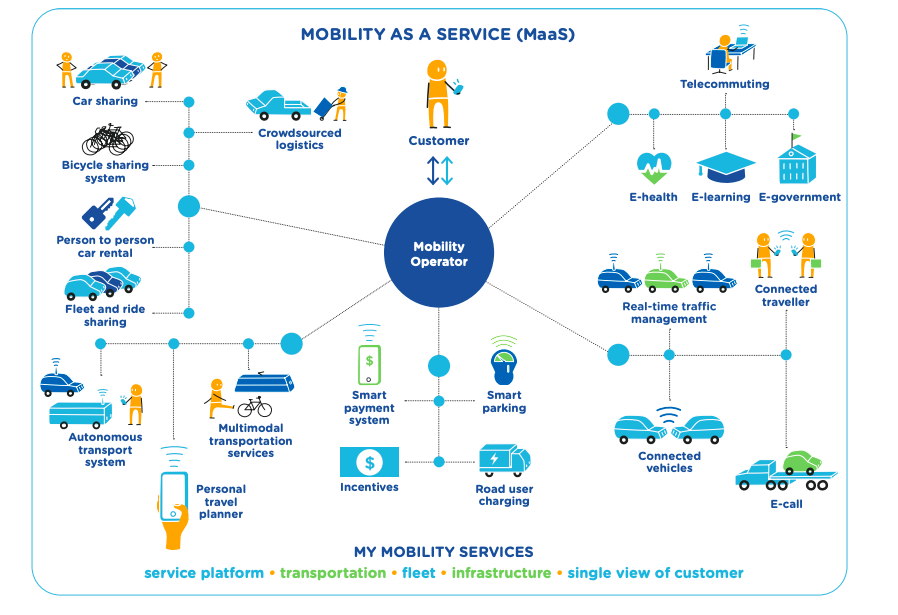

Imagine having a smorgasboard of transport options – from Uber to cabs, e-scooters, autonomous vehicles, buses, trains and more – available for commuters to access and pay for on a single platform, allowing them to tailor their trips seamlessly, taking cars of the roads and emissions out of the air.

That’s the promise of what many are hailing as the brave new frontier in urban transport known as Mobility as a Service.

Professor Hensher is director of the Institute of Transport and Logistics Studies (ITLS) in The University of Sydney and one of Australia’s leading experts on MaaS

He describes MaaS as both an ecosystem and a packaging strategy that has the potential to change behaviour in a way that will bring benefits to communities, the environment and public transport providers.

“There’s a lot of hype at the moment around MaaS because it sounds exciting, it sounds sexy. And because it’s driven by a digital platform governments are very interested in it,” he tells Government News.

But there are still hurdles to be overcome, including questions around governance, ownership, regulation, who ultimately benefits and how to make the system financially sustainable.

Sustainable urban mobility

Driven by a desire for sustainable urban mobility and a boom in app based transport access services, the term Mobility as a Service was first used by Finnish innovator and entrepreneur Sampo Hietanen who founded the world’s first MaaS provider, MaaS Global, in 2015.

Hietanen saw MaaS as not only a paradigm-changer, but a way of cutting costs, increasing transport network efficiency and reducing congestion and greenhouse gasses.

In its recent report on Urban Transportation, AHURI says MaaS doesn’t just include traditional public and private transport, but also leverages disruptive modes such AVs, electric micromobility (e-bikes and e-scooters), car sharing and ride hailing services.

“Typically MaaS is conceived as a single seamless offering that combines different types of mobility services accessed through one digital platform (principally a smartphone), so as to offer a demand-responsive alternative that begins to approximate the convenience of travel for long-distance journeys by private car in uncongested road networks,” AHURI says.

“MaaS is a fluid concept, offering not only transport for people but also goods, and a multiplicity of modes on a ‘plug-and-play’ arrangement.”

From Finland with love

It’s not surprising that Finland, a world leader in the development of mobile phone technologies, has been at the forefront of MaaS.

Hietanen’s firm MaaS Global offers the WHIM app, which is currently being trialled in four European cities (Helsinki, Birmingham, Antwerp, Vienna) and is about to be launched in Singapore.

MaaS could be a useful tool for public transport providers that are increasingly looking towards on-demand and multimodal transport solutions to help expand the reach of their public transport networks.

Infrastructure Australia

In Australia, Victoria and NSW have both included MaaS in key transport policy documents.

NSW’s Future Transport Strategy 2056 lists MaaS as a direction to investigate, saying it can potentially “free up roadside space for pedestrians, bike riders and future transport modes”.

Data drawn from customers via a MaaS platorm can not only offer more personalised services but can link customers to non-travel related products including restaurant delivery, event ticketing and retail, the strategy says.

TfNSW also says MaaS can also make public transport more attractive, citing a Swedish trial that showed 10 per cent increase in public transport patronage during the trial.

Meanwhile, the Victorian Department of Transport’s strategic plan 2019-23 seeks to develop a “digital one stop shop” for transport, and develop better information and interchanges to foster the use of multiple transport modes, while the Queensland government has established a MaaS project office.

Infrastructure Australia says the transport sector risks becoming financially and environmentally unsustainable but technology is changing the way transport is being delivered.

“MaaS could be a useful tool for public transport providers that are increasingly looking towards on-demand and multimodal transport solutions to help expand the reach of their public transport networks, and fulfil the first- and last-mile transport needs of passengers,” the audit says.

“The impacts of MaaS could be accelerated and multiplied when coupled with other emerging technologies, particularly automated vehicles.”

Infrastructure Australia also notes, however, that while elements of MaaS already exist in Australia, no jurisdiction offers a common framework to enable private and public sector actors to work together.

MaaS trialed in Australia

The first MaaS trial of its kind in Australia, led by Professor Hensher and IAG (which provided participants), app developer SkedGo and the iMOVE CRC, was launched in Sydney in 2019 and ran for two years.

It aimed to test appropriate transport service mixes and commercial viability as well as gathering first hand experience of app users.

Somewhat soberingly, a report released in March found that travellers appeared to see very little value in MaaS in the presence of existing apps, such as Opal Connect and Google Pay, without a monetary incentive.

Recently, as reported by Government News, the Queensland government announced the launch of a Brisbane-based MaaS trial available to UQ students and staff.

That trial will run for 12 months and will test the ability to plan, book and pay for multi-modal trips via a smartphone app.

MaaS in the regions

MaaS is largely seen as an urban solution and how to make it both beneficial and sustainable in less populated areas is yet to be tested.

Professor Hensher, who is working with TfNSW to come up with a blueprint for a regional MaaS trial later this year, says the unique needs of the regions have to be considered.

“In urban areas it’s got to do with reducing car use with negative impacts but in rural areas its got more to do with wellbeing and social exclusion,” he tells Government News.

“You’re aiming to provide access to a broader set of mobility options so you’re less constrained in terms of what’s available for you to use that you maybe can’t afford.

“We will be considering with Transport for NSW locations where it’s might make sense to do a trial when we’ve identified where the need is.“

The location of the trial is yet to be decided but Orange, Lismore or southern NSW could provide appropriate settings, he says.

Elephant in the room

Professor Hensher says while governments are, and should be, looking at MaaS, there’s an elephant in the room that can’t be ignored.

“One of the things we concluded from our trial was unless there are financial incentives it’s not going to actually change behaviour,” he says.

“The big question about this is who’s going to provide the financial incentive?

“There are two ways to do it, either you have government providing subsidies to the MaaS programs or you find that the people who are providing the transport services are willing to invest money themselves and take a risk on it being commercial.”

At present, MaaS applications around the world are backed by venture capital, Professor Hensher says.

“In other words someone’s hoping one day they’re turn a profit but don’t hold your breath.

If the objective is to achieve societal outcomes then the government’s got to seriously think about how it can provide some support, and at the moment they’re not interested.

Professor David Hensher

“So it does mean that if the objective is to achieve societal outcomes then the government’s got to seriously think about how it can provide some support and at the moment they’re not interested.

“The reason they’re not interested is they believe the market should determine the MaaS products.”

Where to from here?

The message to government, Professor Hensher says, is that policy needs to move beyond the current technological fixation towards an ecosystem approach, including a financial incentive plan that makes MaaS attractive to communters.

“The government either needs to find a mechanism to do it themselves or they need to find other people to do it,” he says.

This could involve moving away from multimodal to a multi-service model, which means looking for participants in the ecosystem who can provide services other than transport, for example a retail outlet that could offer discounts or products to MaaS subscribers.

“A classic example of a multi services model is in Japan where they cross-subsidise those services and can keep the fares a bit lower by running hotels around the station, and the rents are used to support the railway.”

Professor Hensher says for MaaS to become a valuable proposition, it also has to be more than just another trip planner.

“For MaaS to be successful for the government and general society, it needs to actually have an impact on people’s travel behaviour,” he says.

“If it does no more than provide the convenience of the app and it doesn’t change behaviour, then one has to wonder what the value proposition is.”

Comment below to have your say on this story.

If you have a news story or tip-off, get in touch at editorial@governmentnews.com.au.

Sign up to the Government News newsletter